How Applications Talk to Drivers

Start with two simple questions an application developer and a driver developer often ask:

- As an application developer, do I need to know which exact device my browser will run on — a single device or every device?

- As a device driver developer, do I need to know which exact application will use my driver — one app or every app?

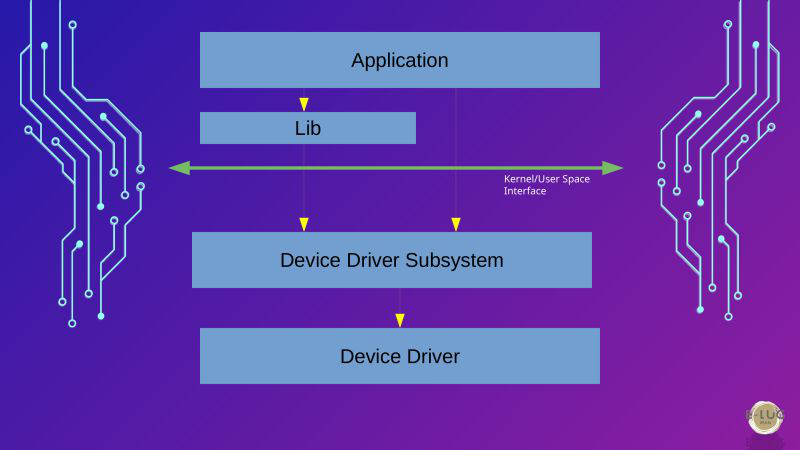

The short answer is no. Apps must interact with devices (for example, a browser needs a socket), but app authors should not and do not have to call device-specific functions directly. That job belongs to the driver. The glue between the two is the Driver Subsystem.

The idea in one line

Applications call standard APIs (e.g. socket()); drivers register their implementations behind generic hooks; the subsystem routes the app’s request to the correct driver implementation.

How it works (informal flow)

- The application calls a public API — for networking, something like

socket()from libc. - The call enters the kernel and reaches the Driver Subsystem, the layer that manages generic device APIs.

- The subsystem finds which driver should handle this request (e.g. the network driver for the active NIC).

- The subsystem calls the function the driver registered for that operation (a function pointer such as

my_netdev_opensocket). - The driver runs its code and performs the device-specific work (opening a socket, allocating buffers, talking to hardware registers). The result returns back through the subsystem to the app.

Function pointers — the essential trick

Drivers expose their capabilities via a table of function pointers. The code looks roughly like: dev->opensocket = &my_netdev_opensocket;

When the subsystem needs to open a socket for that device, it calls dev->opensocket(...) without knowing which concrete function that is. That indirection decouples app-facing APIs from vendor-specific implementations.

Why this matters

- Apps stay portable — same

socket()works across different hardware. - Drivers stay focused — they implement device behaviour and register it; they don’t embed app-specific logic.

- Portability & maintenance — to support a new board you only change the HAL/driver registration, not all apps.

Small practical notes

- Sometimes drivers and userspace are tightly coupled (printer drivers or dedicated user-space drivers); that’s a special case.

- The example above omits many kernel details (namespace lookup, device tables, locking, error mapping) — the goal is to show the overall pattern. For deeper reading, check materials on the Linux Device Model and driver ops tables.