Paper Memory

I started thinking about reading a program from an unconventional type of memory — paper.

It reminded me of punched cards, but since that hardware isn’t available, I went for the next best thing: an A4 sheet.

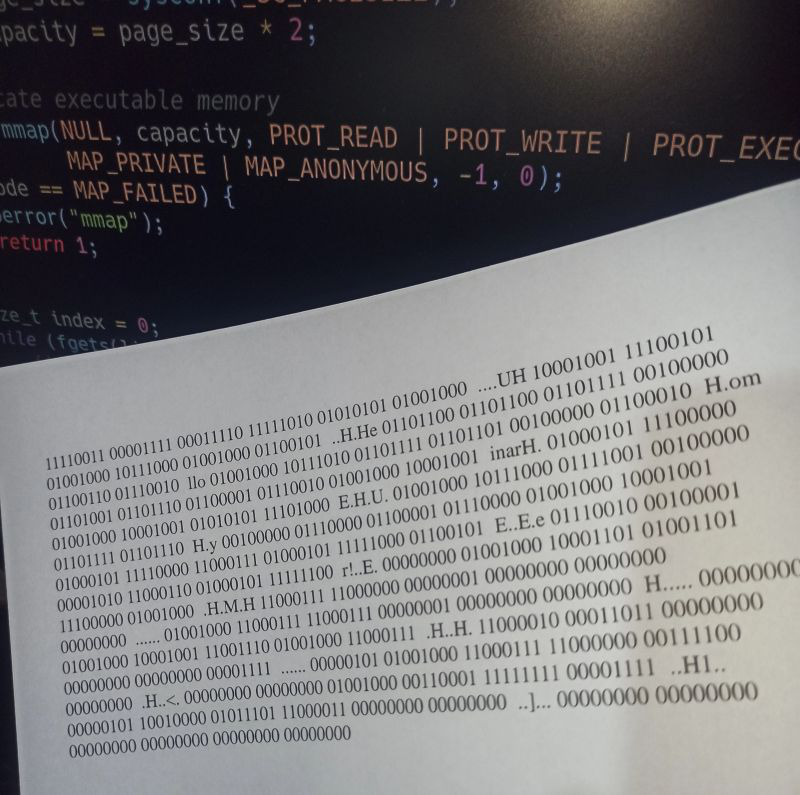

I wrote a simple C program, compiled it into a binary, and printed its bytes onto paper.

Then I wrote another program that reads those bytes back through image processing and streams them directly into RAM for execution — without saving them anywhere.

Everything looked fine until I hit the inevitable segmentation fault.

After some digging, I realized the problem was in my assumption: the binary I was trying to execute wasn’t just “pure code.”

It was an ELF binary — a structured file format containing not only executable instructions but also headers and metadata.

When I loaded the entire ELF image into memory and jumped to it, the CPU started executing header data as code, which obviously caused chaos.

In a normal boot or program launch, it’s the ELF loader that:

- Parses ELF headers

- Maps loadable segments to proper addresses

- Performs relocations

- Applies permissions (read/write/execute)

- Transfers control to the actual entry point

By skipping that process, I was effectively trying to run garbage.

The Fix — Go Flat

Instead of using a full ELF, I generated a flat binary — no headers, no metadata, just raw opcodes from the .text section.

Using options like ld -Ttext=0x0 -nostdlib, I built a self-contained image that doesn’t depend on libc or startup code.

Now, the bytes printed on paper represent pure executable instructions.

When the printed data is scanned back:

- The program reconstructs the binary stream using image processing

- Allocates executable memory via

mmap(PROT_EXEC) - Writes the reconstructed bytes directly into that buffer

- Jumps into the buffer — executing code straight from paper

In this setup, no new process is spawned; the interpreter executes the paper program inline.

Key Notes

ELF ≠ raw code.

The ELF format includes metadata, section tables, and relocations. It cannot be executed by simply loading it into memory and jumping to address zero.Flat binaries work, but they’re minimal.

No startup routines, no libc, no relocations — just bare opcodes. Perfect for controlled experiments, not general-purpose execution.Bit accuracy matters.

One wrong pixel or OCR error can corrupt an instruction. You’ll need robust image recognition or error correction (ECC) if you want this to be reliable.Memory execution permissions.

Modern OSes enforce security like W^X and DEP. Mapping writable+executable memory is restricted, so this should only be done in sandboxed environments.Loader vs Flat.

You can either implement your own ELF loader or work with flat binaries. The former is educational but complex; the latter is simpler but limited.Educational value.

This experiment is not practical but conceptually powerful. It demonstrates the separation between file format and execution image, and why loaders and linkers are essential.

Takeaway

Printing a binary and executing it from memory is more than a hack — it’s an exercise in understanding how systems treat code, data, and structure.

If you want reproducibility, choose one of two paths:

- Implement a lightweight ELF loader

- Or build position-independent flat binaries

Both approaches teach you exactly where execution really begins.