Understanding Thread and Kernel Mode Transition

When we talk about threads in Linux, every process can have one or more of them.

In a simple program, there’s usually just one — the main thread.

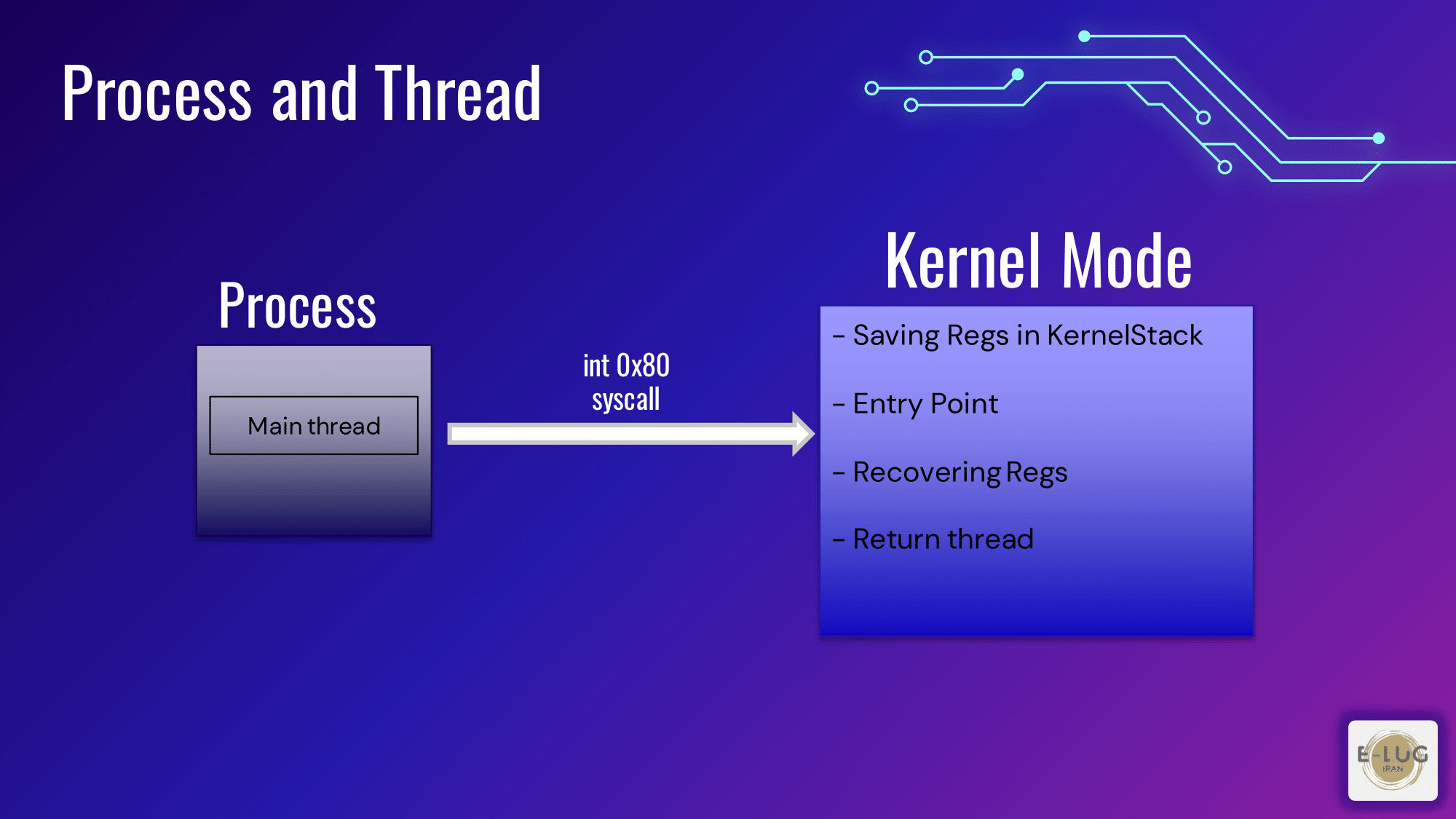

Threads usually run in User Mode, but sometimes they need to switch into Kernel Mode — for example, when they call a syscall to read or write a file.

How the switch happens

When a thread is created using something like pthread_create, the kernel allocates a kernel stack for it.

This memory region is used when the thread moves from user space into the kernel.

Before entering Kernel Mode, the thread must save its current state — things like the instruction pointer, registers, and process information.

These details are stored inside a kernel data structure that also keeps track of which process the thread belongs to.

Then the CPU registers are saved on the thread’s kernel stack.

This is important because these registers hold execution context — for example, the address of the next instruction that should run once we come back to user mode.

Entry point and syscall handling

After saving the context, the CPU jumps to the kernel’s entry point.

Here, the kernel checks what kind of request this thread made — was it a syscall, an interrupt, or something else?

If it’s a syscall, it’s routed to the correct handler.

This is where the kernel executes privileged operations like interacting with hardware, writing to files, or scheduling I/O.

Returning back to user mode

Once the work is done, the kernel restores the saved state from the thread’s kernel stack.

All registers are reloaded with their previous values so that the thread can continue from exactly where it left off.

Finally, instructions like sysret or iret are executed to switch the CPU privilege level back to user mode.

This transition is what allows a normal user-space program to safely use kernel services without breaking system protection.

A note on context switching

This process of saving and restoring a thread’s state is called a context switch.

It doesn’t always mean switching between two threads — even a syscall that temporarily enters the kernel and comes back is a kind of context switch.

Each thread has its own kernel stack, which keeps the transition isolated and safe.

By handling registers and context carefully, the kernel ensures that once the thread returns, it behaves as if nothing happened — except that its request was completed successfully in Kernel Mode.